Study Shows How Mars' Gravitational Pull Influence Earth’s Climate Cycles

16 Jan 2026 15:53:10

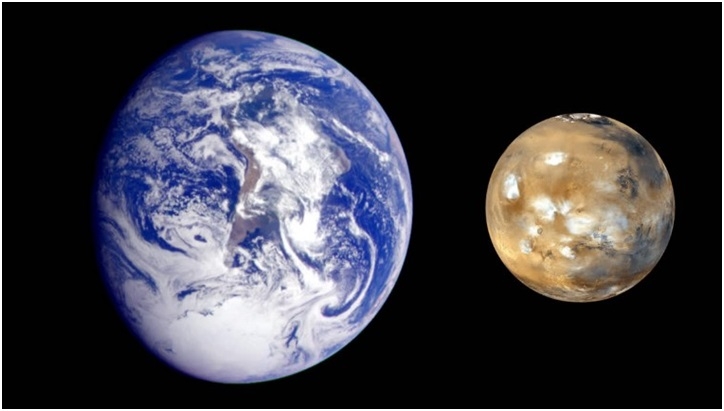

Mars is almost half the size of Earth and carries only one-tenth its mass, and keeps an average distance of around 225 million km from our planet. However, its gravity still affects Earth, driving long-term climate patterns, including ice ages.

Earlier studies suggested that sediment layers on Earth's ocean floor reflect climate cycles influenced by Mars. Now, new research led by the University of California, Riverside, explores the impact the red planet has on our planet.

“I knew Mars had some effect on Earth, but I assumed it was tiny,” said Stephen Kane, a professor of planetary astrophysics at UC Riverside. “I'd thought its gravitational influence would be too small to easily observe within Earth’s geologic history. I kind of set out to check my own assumptions.”

Beginning as a project to verify doubts about recent studies that tie Earth's ancient climate patterns to gravitational nudges from Mars, the new study employed computer simulations to model the solar system’s dynamics and the long-term variations in Earth’s orbit and axial tilt that affect how sunlight reaches the planet’s surface over tens of thousands to millions of years. These orbital and axial shifts, known as Milankovitch cycles, are fundamental to understanding the timing and mechanisms behind the onset and retreat of ice ages—a long period during which the planet has permanent ice sheets at the poles. Notably, Earth has gone through at least five major ice ages over its 4.5-billion-year history, with the most recent being around 2.6 million years ago and is still ongoing. One significant cycle, influenced mainly by Venus and Jupiter, spans 4,30,000 years and alters Earth's orbital shape—transitioning between circular and elliptical. Kane's simulations confirmed that this cycle remains unaffected by the presence of Mars. However, two other critical cycles of 1,00,000 years and 2.3 million years were eliminated when Mars was removed from the simulations.

The Red Planet’s Gravitational Reach

Kane's research revealed that Mars has a measurable effect on Earth's orbital characteristics, including eccentricity (the shape of the orbit) and axial tilt (obliquity). The gravitational influence of Mars is more pronounced due to its distance from the Sun, allowing it to "punch above its weight". Interestingly, the simulations showed that increasing Mars' mass leads to a decrease in the rate of change of Earth's axial tilt. This suggests that a more massive Mars would stabilise Earth's tilt, affecting climate patterns.

Implications for Life Beyond Our Solar System

The paper, published in Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, indicates that small outer planets in other solar systems could similarly influence the stability and climate of Earth-like planets, raising questions about the conditions necessary for life and the evolutionary paths of species.

The simulations suggest that even small outer planets in other solar systems could be quietly shaping the stability of worlds that might host life. “When I look at other planetary systems and find an Earth-sized planet in the habitable zone, the planets further out in the system could have an effect on that Earth-like planet’s climate,” Kane said.

The results also raise other questions about how Earth's evolution might have differed without Mars, as the cycles driven by the red planet have implications for climate changes that have shaped key evolutionary developments in humans and other species.